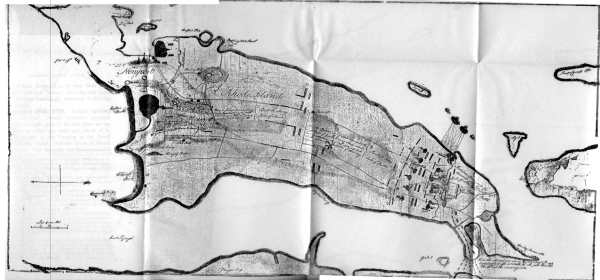

Battle of RI map; Angell, Israel. Diary of Colonel Israel Angell Commanding the Second Rhode Island Continental Regiment during the American Revolution 1778-1781. Edited by Edward Field. Providence: Preston and Rounds, 1899.

Israel Angell's Diary of Aug. 29, 1778

Samuel Ward's writing of Aug. 29, 1778

Jeremiah Greenman's Diary of Aug. 29, 1778

Nathanael Greene's letter to George Washington Aug. 31, 1778

When on 24 August, Gen. Sullivan learned from Washington of the hundred British vessels that were headed toward Newport, his council of war decided the army should withdraw to the fortifications near Butts Hill at the north end of Aquidneck Island and wait there until they learned whether or not d'Estaing would return. Two days later they hurried Lafayette off to Boston by horse to sound out d'Estaing. (He rode the seventy miles in seven hours.) At 9:00 P.M. on 28 August, NG [Nathanael Greene] led off from the trenches outside Newport with the first contingent up West Road. By midnight the last of the troops had withdrawn, and by 3:00 A.M. they were pitching their tents near Butts Hill, without having been detected by the enemy. While the men snatched a little sleep, Sullivan and his officers planned their defense against what they were forced to assume would be a British attack.

Somewhat south of Butts Hill, Sullivan deployed his army of five to six thousand men along a fortified line almost two miles long which stretched across Aquidneck Island from East Passage on the east to Narragansett Bay on the west. Gen. John Glover's brigade was stationed on the left, near East Road and facing Quaker Hill, his left flank protected by Gen. John Tyler's Connecticut militia. To Glover's right, in the center, was a brigade temporarily under Col. Christopher Greene, NG's kinsman and hero of Red Bank, who had been shifted from his usual command of the Black Regiment. Butts Hill stood to their rear. To Col. Greene's right, the line was extended to West Road by Col. Ezekiel Cornell's R.I. Brigade. Across West Road from Cornell, facing Turkey Hill to the south, was Gen. James M. Varnum's brigade, flanked on the far right by Col. Henry Brockholst Livingstone's regiment. Holding a redoubt on the far right was Christopher Greene's Black Regiment, now under NG's longtime friend, Maj. Samuel Ward, Jr. NG was in command of the entire right wing. Three miles in front of the line, Sullivan posted the light infantry unit of Col. John Laurens on West Road and that of Col. Henry Beekman Livingstone on East Road.

It was daybreak before the British commander, Gen. Robert Pigot, learned that the Americans were gone. He immediately sent sent Gen. Francis Smith with several regiments up East Road in pursuit and Gen. Friedrich Wilhelm von Lossberg with Hessian and Anspacher battalions up West Road. Gen. Prescott was assigned to take over Honeyman's Hill.

In the early morning hours of 29 August, there was brisk fighting between these two advancing columns and Sullivan's advance units. For a while Col. Henry Beekman Livingstone and his men on East Road bought Gen. Francis Smith's Regiments to a virtual standstill by firing from behind trees and then falling back. When Smith was reinforced, Livingstone was forced to fall back. Along West Road, Col. Laurens, using similar tactics, struck savagely at von Lossberg's Germans. Before their superior firepower Laurens slowly retreated to Turkey Hill, then finally back to NG's sector. Progressing northward on East Road, Gen. Smith took Quaker Hill to the south of American lines, then began assaulting Glover's sector. Smith met with such sustained fire from Glover's artillery and small arms that the British were forced to withdraw with considerable losses. Smith's subsequent artillery bombardment from Quaker Hill failed to dislodge Glover.

A lull in the British attacks at mid-morning led NG to propose that Sullivan launch an all-out attack against the enemy. Sullivan vetoed the proposal and, as NG later admitted in a letter to John Brown he "believd the General had taken the more prudent measure." Soon, three British frigates and a brig started bombarding American lines from Narragansett Bay but sailed back when NG managed to train two 18-pounders and two 24-pounders against them. In the meantime, von Lossberg had attempted to outflank Samuel Ward's redoubt near the west end of the island; in fierce hand to hand fighting, the Black troops twice repulsed von Lossberg.

At about 2 P.M. von Lossberg, now reinforced, made an all-out attempt on NG's wing. Advancing past Ward's redoubt, he made some inroads against NG's regiments. But NG counterattacked with the aid of two additional continental regiments (one, the Second Rhode Island, under his old friend, Israel Angell), Solomon Lovell's Massachusetts Militia, and Col. Henry Beekman Livingstone's light corps. With musket and bayonets, NG's 1,500 troops sent von Lossberg back in confusion. As NG wrote to Washington above: "We soon put the Enemy to the rout and I had the pleasure to see them run in worse disorder than they did at the battle of Monmouth." Sullivan considered an assault on Turkey and Quakers Hills but gave it up because his men had been too long without sleep or food, and they would have been exposed to a heavy artillery barrage before they reached to slopes of the hills. Toward evening there was a final unsuccessful American attempt to surround the Hessian Chasseurs; then the day petered out with an exchange of artillery. The battle of Rhode Island was over.

from:

Greene, Nathanael. The Papers of General Nathanael Greene. Edited by Richard K. Showman, et al. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press for the Rhode Island Historical Society, 1976--. Vol. 2 pg 503-504

from:

Dearden, Paul F. The Rhode Island Campaign of 1778 an Auspicious Dawn of Alliance. Providence: , 1987. pg 157-179

While Angell and his tired veterans sweltered in the heat of New Jersey Colonel Christopher Greene of the 1st Rhode Island, in the cooler climate of his home state, struggled to piece together a battalion of former slaves. When the idea of offering slaves their freedom in return for active service was first suggested all concerned believed the plan would help solve the problem of finding Continental recruits. The General Assembly voted that every able-bodied negro, mulatto, and Indian slave could enlist for the duration of the war with bounties and wages the same as for free men. Once enlisted and approved by the regimental officers the slave would become absolutely free.

Unfortunately the small population of 3331 blacks and Indians could not support the effort adequately. Fewer than two hundred soldiers could be recruited. Finding the scheme expensive and impractical, the legislators reversed themselves. "No negroe, mulatto, nor Indian slave will be permitted to enlist in the Continental battalions after 10 June 1778." Greene and his officers proceeded to train the black infantrymen already signed on. All heard the news that a French fleet was on the way and were looking forward to some heavy fighting in the near future.

General John Sullivan, commanding in the area, was charged with the task of containing the depredations of the 4000 British and Hessian troops occupying Newport and Aquidneck Island. For this purpose he had only the handful of Continentals under Christopher Greene, a brigade of Rhode Island state troops, and several thousand as yet unmobilized militia. In early July orders from General Washington changed Sullivan's mission from defense to attack and thrust the quiet Rhode Island sector into the forefrount of the war.

Admiral d'Estaing arrived off Sandy Hook with an impressive array of powerful ships but could not cross the bar to gain entrance to New York harbor. The French and American leaders then turned their attention to Rhode Island, where a combined ea and land assault might destroy the enemy occupation forces, liberate Newport and open Narragansett Bay to American and French shipping. Sullivan, expected heavy reinforcements, was surprised to observe a British fleet arriving at Newport on 15 July bringing 2000 additional enemy troops to strengthen the garrison. Not until 30 July did Continental units from Washington's army march into Providence. These amounted to but 1200 men in two shall brigades, one of which was commanded by Varnum and included the 2nd Rhode Island. Christopher Greene's small 1st Rhode Island joined its brother battalion in Varnum's brigade.

Discouraged by the small numbers of Continentals made available to him, Sullivan struggled to put together an army. On 1 August Rhode Island called out half her militia, six regiments of 3000 civilian soldiers. The state also provided the most reliable troops besides Continentals in the expedition, 1300 men of the state's brigade, who had enlisted for fifteen months. Six regiments of Massachusetts militia and one from Connecticut were expected to arrive momentarily including artillerymen, 3850 altogether. With 300 Continental artillerymen, 150 New Hampshire cavalry, and 300 boat service troops Sullivan would find himself with 10000 hastily assembled Americans. Hoping for the addition of at least 4000 French soldiers and Marines, the general believed he would have enough men for the task. It would have to be enough. There weren't any more.

To compensate in some measure for the weakness of the force he had sent north and to assist Sullivan in the problems of organizing a new army, Washington detached his two most trusted generals from the main army in New York, and sent them forward as division commanders under Sullivan. A relative of d'Estaing, Lafayette would be able to include French troops in his division. Although Nathanael Greene still held the staff position of quartermaster general, Washington wanted his steady hand in the field where he could guide Sullivan away from hasty, ill-advised decisions. Considering that the expedition against the British at Newport represented the first experiment in French-American cooperation, the commander in chief might better have left Green in command of the army at White Plains and come to Rhode Island himself.

d'Estaing's fleet arrived in Rhode Island waters on the 29 July and

anchored in the open roadstead to the south of Aquidneck Island. The

French admiral fretted at the delay as the American units assembled

from their scattered starting points. After a series of conferences

d'Estaing and Sullivan agreed upon a course of action:

On 8 August the French fleet would enter Narragansett Bay.

On the night of 9/10 August Sullivan would ferry his troops to the

east shore of Aquidneck Island.

At the same time French soldiers and Marines, totaling 4000 men,

would land on the west shore.

British troops stationed in the northern part of the island would be

cut off and subdued.

The combined French and American forces would then move south to attack

the enemy at Newport, supported by the guns of the French fleet.

Major General Sir Robert Pigot commanded the British and Hessian troops on Aquidneck Island. Although an aggressove leader who had sirected successful raids against Bristol, Warren, and Fall River in May, aimed at destroying American landing barges, he had at the same time shown a certain decency in his treatment of women and children. His second in command, Major General Richard Prescitt, had served two separte terms as a prisoner of war in American jails, an experience which left him soured and vindictive. Under Pigot and Prescott Brigadier Francis Smith led the British troops and Major General Friederich von Lossbreg the Hessians. These generals controlled a strong force of more than 7000 men, including British, Hessian, and American Tory troops plus 800 sailors and Marines from the crews of scuttled frigates. Fortifications had been erected to protect Newport against attack from the land side and were occupied by numerous cannon.

The British plan envisioned withdrawal from the northern end of the island to the defenses encompassing the town. Pigot ordered all cattle, horse, and sheep except one milk cow per farm herded into Newport. Carriages and wagons were to be destroyed. All negroes were to be brought in. Orchards and houses blocking fields of fire from the redoubts would be leveled. Such a policy would bring temporary ruin to the island farmers.

sullivan assembled his army in Tiverton, east of Aquidneck. On the morning of 9 August his men began to practice the amphibious assualt scheduled for the next day. As the troops started loading into their assigned boats word came to Sullivan from observers and scouts that the British had evacuated their positions in the northern part of Aquidneck. The General then turned his rehearsal into the actual landing, and his regiments came ashore nearthe abandond enemy redoubts. The Americans hoped the French would follow their example and land alsobefore scheduled. This hope vanished when at noon a fleet of thirty-five sail on the horizon approaching from the south were identifed as British warships and transports. The enemy sailed toward the middle passage into the bay, but at hte last minuteweered off and anchored inthe open roadstead. Alarmed, d'Estaing cancelled his plans for landing troops and ordered his fleet to prepare for sailing.

Early on the 10th the French warships put to sea behind a northeast wind. At their approach the British weighed anchor and withdrew. Both flotillas soon disappeared over the horizon. d'Estaing's abrupt departure taking with him all soldier and Marines left his allies puzzled and concerned. The American leaders had to decide whether or not without French support their motley army or, as Sullivan described it "this indigested body of militia and regulars" could be expected to overcome 7,000 enemy troops waiting behind their fortifications at Newport. As the generals considered the problem the army made camp on the high groud south of Butt's Hill.

On the night of 11-12 August a severe storm struck the area, lasting for two days and laying flat the fields of corn. As the troops began to dry out their leaders reached a decision. The army would advance to the vicinity of Newport and lay seige to the enemy there. No attempt would be made to assault the fortifications until the French returned, an event that all hands accounted to be a certainty.

Long and narrow, Aquidneck Island extends for fifteen miles north and south but only four miles east and west (at its wideest point). Newport lies in the southwest portion fronting ona fine sheltered harbor. Two main roads run parallel from north to south converging just above the town. The center mass of the island is formed by a series of gently sloping ridges. Almoust all of the land was under cultivation and divided into separate fields by numerous stone walls or fences. Hay and corn (that hadsurived the storm) awaited harvesting. Farmhouses and barns dotted the landscape, and here and there orchards and woods which had survived the British axe appeared.

For his advance on Newport Sullivan deployed his forces in three echelons; four brigades in the first, two in the second and one in the third. John Glover's Continental regiments moved cautiously down the east road; on their right the Rhode Island State's Brigade under Ezekiel Cornell. Varnum's brigade including the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island marched down the west road, with a brigade of militia under Christopher Green (as acting brigadier) on their left. The second and third echelons followed

Of the 10000 men in Sullivan's force 5000 were Rhode Islanders. This represented a full mobilization of the state's manpower, considering that 2000 additional militiamen were being held ready for call up. For a year and a half these men and their families endured the cruel British occupation. Their houses burned, their livestock stolen, their friends rounded up and held in enemy prison ships. Their ocean and coastal trade was almost destroyed, their major port shut down. Whether Continentals, State's Brigade, or militia, these Rhode Island soldiers had a powerful incentive to come to grips with their persecutors.

Artillery pieces on wheeled carriages moved forward with the infantry brigades. Heavier cannon on wooden sleds were dragged along by teams of oxen. Slowly and cautiously the Americans approached the British positions. Gun emplacements were constructed within 1000 yards of the enemy lines. Soon the seige developed into an artillery duel. Although the British heavy guns outnumbered Sullivan's seventy-six to seventeen, they were scattered throughout numerous forts and redoubts. Redcoat infantry officers complained that the seamen manning many of their batteries fired constantly with no visible targets. By concentrating their fire on one portion of the enemy defenses the Americans forced Pigot to abandon his forward posts.

On 20 August d'Estaing's fleet returned but anchored in the open roadstead. The Americans noticed that several French ships had been dismasted, including the flagship, and others damaged injuries caused by the storm rather than enemy action. The sad condition of his warships led to d'Estaing to insist on sailing to Boston for repairs. Lafayette and Sullivan could not dissuade him. It was a bitter blow to the Americans, who felt they were on the verge of victory. "could the fleet have cooperated us ... we must have been successful, " wrote Nathanael Greene.

Greatly disturbed, Sullivan criticized the French for their withdrawal in orders published to the army, "The general cannot help lamenting the sudden departure of the French fleet. He yet hopes the event will prove America is able to procure with her own arms that which her allies refused to assist her in obtaining." These hasty words started a clamor against the French and produced a chilling reaction from d'Estaing, neither designed to strengthen the new alliance. Lafayette, defending the actions of his countrymen, was assailed by American officers; "I am more upon a warlike footing in the American lines," he wrote Washington, "than when I came near the British lines at Newport."

The more aggressive officers recommended an all-out assault against the enemy positions, an all-or-nothing gamble to retrieve the situation, but Sullivan ruled against them. By this time, 23 August, several militia units had left the army with others planning to follow. American strength had declined to 8,174 men. There was no reasonable chance of overcoming the 7,000 enemy regulars waiting with numerous cannon behind the fortifications of Newport. When word arrived that the British fleet had sailed from New York with reinforcements for Pigot, the American leaders decided reluctantly to withdraw.

As a first step heavy guns and baggage were moved north. To deceive the enemy, outposts were strengthened and moved forward. Unfortunately a picket of the 2nd Rhode Island, which had established itself to the south near the ocean, was surprised and captured by a British raiding party. Next evening the Americans attacked a Hessian post, causing a few casualties and much alarm. Covered by this activity the American army silently withdrew from its lines on the night of 28-29 August and marched north. The enemy, unaware, made no effort to interfere.

Near the northern end of the island rises an eminence called Butt's Hill, where the American army encamped at the beginning of the operation. It was essential to the success of the withdrawal that this ground be held. About a mile south, toward the enemy, a valley cut across the island. If the British crossed this valley they could threaten the vital high ground. Common sense indicated that a defense be organized to prevent them from so doing. As Sullivan's tired men arrived in the area early in the morning of the 29th, a jumble of units developed with men lying down and going to sleep wherever their regiments first stopped. The impetus of the withdrawal carried the army close to Butt's Hill and away from the Valley.

After daylight attention began to focus on defending the valley. Nathanael Greene, commanding the brigades on the right, was responsible for stopping the enemy advance along the west road. To do so he sent one of Varnum's battalions, the 1st Rhode Island, forward or south about a half-mile to a small hill which dominated the western portion of the valley. Also on the hill was located an artillery redoubt which housed a number of American cannon. Across the valley at a distance of about a mile loomed an eminence called Turkey Hill, which the enemy was sure to occupy. Greene held his other units back to await developments.

On the left or east Brigadier General Glover led his own and Christopher Greene's brigades. Lafayette, who normally commanded there, had been sent to Boston to plead with d'Estaing for French troops. Glover moved his men forward of Butt's Hill for about a mile, where he placed them behind stone walls covering the eastern portion of the valley. Opposite Glover rose Quaker Hill, at 280 feet the highest terrain feature in the area. Colonel Crane moved cannon into position all along the American line. At this point the island measured only one and three quarters miles from east to west.

Sullivan positioned covering forces three miles forward of the valley, where a cross-island road ran from east to west. Most of the troops for these forces came from Jackson's battalion of Glover's brigade, but the leaders were officers from Sullivan's staff who had volunteered for the assignment. Colonel Henry B. Livingston, who commanded the detachment guarding the road junction on the east road, had come north from Washington's staff to help Sullivan run his expedition. On the west road were three of the more combative officers in the army, "Colonel" John Laurens of South Carolina, Washington's aide and son of the President of Congress, who had repeatedly refused to accept a commission, Major Silas Talbot, recovered from wounds received at Fort Mifflin and recently promoted, and Colonel Francois Louis de Fleury, Frenchman and engineer, who like Lafayette had come to America to fight and not merely to collect his pay. These officers deployed their men in concealed defensible positions and awaited the inevitable the inevitable advance of the Redcoats. Between these covering forces and the main army a regiment of Massachusetts state troops formed itself into an outpost line of resistance or picket.

After daylight on the morning of the 29th British soldiers from their trenches and redoubts could see that the American positions had been abandoned. General Pigot promptly ordered his general to pursue the rebels but cautioned them not to bring on a general engagement. Prescott's two regiments moved into the area from which the American batteries had been firing. Brigadier General Smith with two regiments led by 240 light infantry proceeded along the east road, headed for Quaker Hill. Major General Lossberg with two Hessian regiments led by 200 chasseurs marched out along the west road toward Turkey Hill. Captains Coor and Trench of the light infantry and Captains Malsburg and Noltenius of the chasseurs were aggressive officers whose men were all spoiling for a fight. The three brigades left the Newport lines at six-thirty o'clock.

The chasseurs came under American fire first. They attacked and were able to overrun a small outpost, but as they approached Laurens's main position they began to suffer casualties and came to a halt. The Americans waited until the enemy column had deployed, then began to pull back. Even at this early hours soldiers began to suffer from heat and thirst. Malsbergreported that a wounded American prisoner who asked for water was told the chassuers had none to spare.

Hearing the firing at Redwood's Mill, scene of the Hessians imbroglio, General Pigot sent Huyne's Hessians and Fanning's Tories to reinforce Lossberg and although Smith's column had not yet made contact ordered up the 54th from Prescott's force and Brown's Tories to their assistance. The British commander committed six of his ten regular regiments plus the Tories, altogether 3,900 men out of the army's total of 7,100. Soon the light infantry on the east road, advancing without flank protection came under fire from Livingstone's well positioned troops. A number of Red Coats went down. As Lieutenant Colonel Campbell's 22nd Regiment came up to help it too began to take casualties. Livingstone did not linger. Like Laurens he pulled back to safer ground.

Waiting in the main American positions, General Sullivan heard the firing ahead. He ordered a regiment sent forward on each road to support the covering forces, a puzzling move as he had no intention of holding the forward ground. He then sent word to withdraw all advance troops to the main line. This last directive had the effect of turning a fighting withdrawal into a kind of rout. As the 13th Massachusetts from Glover's brigade reached the top of Quaker Hill on their way forward, the order to retreat arrived, which they promptly executed. The whole mass of forward troops came fleeing down the hills and into the American lines.

At this point (ten o'clock) it seemed to the British that they had swept all before them, which in fact they had. As the light infantry, followed by the 22nd and 43rd, advanced down Quaker Hill into the valley they came under cannon and musket fire from Glover's positions behind the stone walls. Additional Redcoats went down, including Colonel Campbell's nephew killed at the colonel's side. British cannon firing from Quaker Hill were too far off to be effective. The attackers were brave men, and other regiments were coming up, but Pigot had told his generals not to bring on a general engagement. "It was thought inadvisable to attack them further," said a British staff officer. General Sullivan described these events in laconic phrase; "The enemy advanced on our left very near, but were repulsed by General Glover. They the retired to Quaker Hill."

The sky was clear, the sun shining, and the temperature hot. Men suffered from thirst and heat exhaustion. Captains Malsberg and Noltenius with their chassuers had reached Turkey Hill and in spite of the heat were strongly inclined toward continuing the attack. They had a reputation for aggressiveness to maintain, particularly compared to the British light infantry. No senior officers appeared to dissuade them. They led their men, reduced in number by casualties, down into the valley. There they drove back the remnants of the American covering force, and themselves took shelter behind a stone wall to reorganize.

Nathanael Greene and Varnum, watching from Butt's Hill, saw the Hessians enter the valley. In response the two generals sent forward the 2nd Rhode Island and another regiment to reinforce the troops already defending the artillery redoubt. Israel Angell, commanding the 2nd Rhode Island, described the action: "I was ordered with my regiment to a redoubt on a small hill, which the enemy was a trying for, and it was with difficulty that we got there before (them)." At the same time the chassuers left the protection of their wall and advanced up the hill toward the redoubt. "we found" Malsberg reported, "obstinate resistance, and bodies of troops behind the work (redoubt) and at its sides, chiefly wild looking men in their shirtsleeves, and among them many negroes." These were the black soldiers of the 1st Rhode Island.

After suffering casualties, including Captain Noltenius wounded, the Hessians fell back to the valley floor. General Lossberg, watching the fight from Turkey Hill, ordered Huyne and Fanning to move forward as reinforcements. When these regiments had deployed on either side of the chassuers, the enemy had more than a thousand men committed to the attack on the redoubt. At about the same time two British frigates sailed close to shore in an effort to shell the American positions. The situation had the illusion of crisis, but Lossberg's effort lacked the strength to overrun Nathanael Greene. A British officer present described the outcome of the waterborne attack; "Vigilant fired a few rounds at the rebels in front of the artillery redoubt but was driven off by rebel cannon fire from the ... redoubt and Arnold's Point."

Seeing reinforcements moving down from Turkey Hill Greene committed the remaining regiments of Varnum's brigade to the fight to save the redoubt, ordered Cornell's brigade to move up on the left of Varnum, and from the second echelon called up Lovell's brigade of Massachusetts militia, altogether more than 2,500 soldiers. Varnum's men and Cornell's were to the left of the redoubt, Lovell's to the right, extending to the west shore of the island. Malsburg reported the result; "Huyne and Fanning (were) in line with the Chassuers. The enemy was advancing on our right flank. More American reinforcements arrived. Superior numbers of the enemy caused our withdrawal to Turkey Hill." General Sullivan wrote, "The third time the enemy attacked with greater numbers. Aid was sent forward. There was a short conflict for an hour. Cannon fired on both sides from the hills. The enemy fled to Turkey Hill, leaving his dead and wounded." It was then four P.M. The fighting was over.

There had been lots of firing, but most of it at long range. Casualties were not heavy. Major Ward, who in the absences of Christopher Greene had led the 1st Rhode Island, reported, "One captain slightly wounded in the hand, a couple of blacks killed, and four or five wounded, but none badly." It seems incredible that Ward could not have ascertained exactly the number of his men injured, considering he had not many more than one hundred. Angell was even less specific than Ward; "I had three or four men killed and wounded today." Most American casualties occurred among the covering forces. Sullivan reported for the army 211 soldiers, killed, wounded, and missing, in view of the uncertain measures used in accounting for American losses a doubtful figure. Pigot recorded 260 British, Hessian and Tory casualties, most of them in the light infantry, the 22nd, the chassuers, Huyne's and Fanning's. Sullivan claimed that enemy losses were greater, but there is no hard evidence for doubting Pigot's figure.

Through the night of the 29-30th of August and the following day the two armies remained in place, exchanging long range artillery fire. On the night of the 30-31st Sullivan quietly withdrew his brigades from the island moving them by boat to Tiverton and Bristol. The British did not try to interfere. Arrived on the mainland many of the militia regiments returned to their homes. Varnum's Continental brigade with the 1st and 2nd Rhode Island took over the protection of Bristol and Warren, Glover's brigade, Providence, Cornell's Rhode Island State troops, Tiverton, and Christopher Greene's dwindling militia force, East Greenwich on the west side of the bay.

On 1 September Sir Henry Clinton arrived at Newport with seventy vessels carrying ten regiments of infantry and two brigades of artillery. Sullivan complained to General Washington that his army was "now reduced to 1,200 Continentals and about 2,000 state troops and some militia. (There are) 11,000 enemy and extensive coastline to defend." On 4 November Admiral d'Estaing left Nantasket Road off Boston with no hint to anyone as to his plans or destination.

The expedition failed. Newport and Aquidneck Island remained under the despot's heel. After a heated argument with Clinton over the conduct of the British defense, Pigot returned to Great Britain, leaving command of the forces in Rhode Island to the hated Prescott. British Major MacKenzie wrote that General Pigot departed "with the goods wishes of all the Garrison, having treated every person under his command ... with civility and attention, so natural to men of good sense and polite education." The American failure generated quantities of rhetoric by those seeking to place the blame on the French or other scapegoat. Many seemed to forget the act of God which put the French fleet out of action and doomed the expedition. The 1st and 2nd Rhode Island maintained their reputation for steady fighting and were reconciled to more years of hard service, until the chance would come again to capture a British army.

from:

Walker, Anthony. So Few The Brave (Rhode Island Continentals 1775-1783). Newport: Seafield Press, 1981. pg 50-67

On the night of the 28th the American forces silently withdrew from the entrenchments, and the entire army marched rapidly toward positions prepared on the hills at the northern end of the island. The following morning the British obtained possession of Turkey and Quaker Hills, and artillery having been brought up, an attempt was made to force the American lines at Barrington and Butts' Hills. General Greene taking advantage of the fact that the enemy had advanced too quickly, and was not well supported, and not superior in numbers to his own division, attacked and drove them from the advanced position they had taken. The two main roads from Newport to the Ferry, known as the East and West roads, passed respectively over Quaker and Butts' Hills, and it was along these roads the pursuit had come. The American battle was formed with Livingston and Tyler on the extreme western and eastern flanks respectively, with Varnum's brigade on the right of the line. Here was the regiment commanded by Colonel Angell, although earlier in the day his command had been used to retake the redoubt on the western extension of Butts' Hill and to repel an attack made at that point. That appears to have been the "high water" mark of the British pursuit. Then had followed the counter attack by Greene. Next to Varnum's brigade was Cornell's, and on the extreme left was Glover's brigade, and between Glover and Cornell, a brigade commanded by Lieut.-Colonel Christopher Greene, including the battalion of negroes, Indians, and mulattoes known as the Black Regiment. This battalion was commanded by Major Ward, and numbered perhaps as many as 140 men, who behaved as well as any troops who had never before been under fire. With white troops they repelled an assault by the Hessians made with the bayonet. Their part in the fight has been absurdly praised and exaggerated. The British and Hessians were defeated in their attempt to carry the American position. The hottest part of the day's work was between ten o'clock and noon. The cannonade continued the rest of the day, and the British expected a renewal of the attack. Both armies rested expectantly throughout the night of the 29th and day of the 30th. During the night of the 30th without awakening suspicion General Sullivan withdrew the remainder of his forces from the island. General Lafayette, who had been in Boston, returned in time to take command of the rear guard as it was crossing to the mainland.

from:

Lovell, Louise Lewis. Israel Angell, Colonel of the 2nd Rhode Island Regiment. [New York]: Knickerbocker Press, 1921. pg 135-136